Then today the quarterly GDP number came out, and it was 3.5% annualized, when the survey was 3.3%. The market jumped on that news.

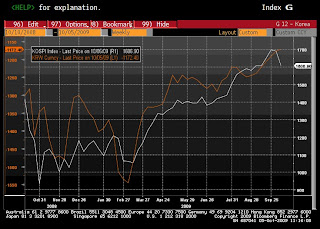

My colleague sent this Bloomberg to me:

geez...i guess people don't care that 3Q GDP already happened - not about the future....

To some extent he's right. Whatever happened in the past happened in the past and is not information about the future. And for asset valuation it is, after all, the future stream of cash flows that matters. It's not: "How well did this company do in the past" but "How well is this company going to do in the future" that should inform how much you should be willing to pay for a piece of it (i.e. a stock.)

However, I'm not sure if I totally agree. Here's a theory of why the GDP release today maybe should matter to the equity markets.

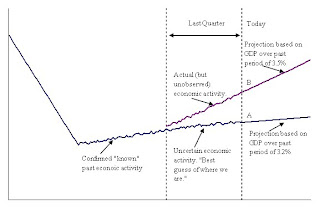

From quarter to quarter we aren't actually sure what economic activity is. We have a sense from various data releases and anecdotal evidence but we rely on official statistics and ultimately on the GDP number to aggregate all these statistics and anecdotal evidence and tell us what economic activity actually was (to the best extend possible--of course GDP is also just a representation of reality and we can't ever truly know economic activity but this is not a philosophy class.)

So what if the entire time the market assumed that economic activity was something and that we are at point A in the diagram below when in reality we are at point B.

That would probably inform your estimate of the future. Even if the economic growth number stayed the same, past, higher economic activity would mean higher profits today and in the future.

That would probably inform your estimate of the future. Even if the economic growth number stayed the same, past, higher economic activity would mean higher profits today and in the future.So is it possible that to that extent the GDP number today matters to market valuation even though it is backward looking and only tells us about what happened in the past?