Friday, November 6, 2009

Unemployment by Education

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Productivity again

Production shows the by now classic green shoots phenomenon: Sure, it's declining, but it's declining at a slower pace.

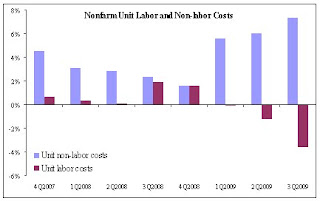

Production shows the by now classic green shoots phenomenon: Sure, it's declining, but it's declining at a slower pace. We can also see that we're not really cutting costs by that much more, depending on the capital to labor mix in the production function. While labor costs are falling, non-labor costs are rising even faster.

It seems too easy an explanation that market participants don't look into these numbers and only look at the headline number but to me this is not reason to shrug off e.g. the CIT bankruptcy and believe the economy is humming along now. Production is still slowing and people work less, which does not spell well for future demand. Is a weak dollar really enough to sustain production and turn it around?

It seems too easy an explanation that market participants don't look into these numbers and only look at the headline number but to me this is not reason to shrug off e.g. the CIT bankruptcy and believe the economy is humming along now. Production is still slowing and people work less, which does not spell well for future demand. Is a weak dollar really enough to sustain production and turn it around?Is greater productivity really good news?

- why keep producing more if unemployment is high and demand is lacking?

- In this environment, where can we see demand coming from?

- Is the low dollar enough to make US exports so competitive that they can support aggregate demand in the US to push production high enough until increased productivity can't take care of demand anymore and you need to hire people back (who will then create demand themselves)?

- Is the market correct in viewing the higher productivity as positive?

A more detailed understanding of the literature on the real business cycle coudl certianly be useful.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Should information about the past still matter to equity prices today?

Then today the quarterly GDP number came out, and it was 3.5% annualized, when the survey was 3.3%. The market jumped on that news.

My colleague sent this Bloomberg to me:

geez...i guess people don't care that 3Q GDP already happened - not about the future....

To some extent he's right. Whatever happened in the past happened in the past and is not information about the future. And for asset valuation it is, after all, the future stream of cash flows that matters. It's not: "How well did this company do in the past" but "How well is this company going to do in the future" that should inform how much you should be willing to pay for a piece of it (i.e. a stock.)

However, I'm not sure if I totally agree. Here's a theory of why the GDP release today maybe should matter to the equity markets.

From quarter to quarter we aren't actually sure what economic activity is. We have a sense from various data releases and anecdotal evidence but we rely on official statistics and ultimately on the GDP number to aggregate all these statistics and anecdotal evidence and tell us what economic activity actually was (to the best extend possible--of course GDP is also just a representation of reality and we can't ever truly know economic activity but this is not a philosophy class.)

So what if the entire time the market assumed that economic activity was something and that we are at point A in the diagram below when in reality we are at point B.

That would probably inform your estimate of the future. Even if the economic growth number stayed the same, past, higher economic activity would mean higher profits today and in the future.

That would probably inform your estimate of the future. Even if the economic growth number stayed the same, past, higher economic activity would mean higher profits today and in the future.So is it possible that to that extent the GDP number today matters to market valuation even though it is backward looking and only tells us about what happened in the past?

Monday, October 26, 2009

Portfolio Management

If you wanted to, you could put that on a scatterplot like the following:

On the horizontal axis would be how much you are overweight or underweight (for let's say a certain sector) and on the vertical axis would be how much that sector out- or underperformed the broader market. You'd have a point for each time period, like for each month or quarter or over whatever investment horizon you make your decisions.

Your optimal graph would look something like this, where most of the time you are overweightin the sectors that outperform and underweight in the sectors that underperform.

If, however, you're an unnamed asset management firm then your graph looks like this:

If, however, you're an unnamed asset management firm then your graph looks like this: I have no idea how that stacks up against other asset managers but there are essentially two possibilities:

I have no idea how that stacks up against other asset managers but there are essentially two possibilities:a) This firm is not that great at selecting the right assets (and outperformance comes from something else, e.g. liquidating when the market tanks, luck, who knows?)

b) Everyone is like this corroborating a theory that asset prices operate in a very complex system and that nobody really has the means to make good educated guesses which assets are more likely to outperform.

c) Everyone is like this but the picture is misleading and even a small margin of better bets vs. worse bets leads to outperformance over the long-run.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

The Uncanny Valley

"like to study other human faces, and they also can enjoy scrutinizing countenances that clearly are not human, such as a doll's or a cartoon figure's. But when an image falls in between -- close to human but clearly not -- it causes a feeling of revulsion. [...]

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the uncanny valley as a valid phenomenon, there are no clear explanations for it, Ghazanfar said. One theory suggests that it is the outcome of a "disgust response" mechanism that allows humans to avoid disease. Another idea holds that the phenomenon is an indicator of humanity's highly evolved face processing abilities. Some have suggested the corpse-like appearance of some images elicits an innate fear of death. Still others have posited that the response illustrates what is perceived as a threat to human identity."

The same is apparently true with monkeys. How interesting. This was via Marginal Revolution.

Earnings season again

- Yes, unemployment is a lagging indicator but two-thirds of the US GDP (as you'll remember form Econ 101 GDP=C+I+G+[X-IM]) comes from private consumption (C.) While government support for consumption (e.g. cash for clunkers) supports/supported consumption these programs run out. With close t0 10% unemployment and only a slowing in the new unemployment numbers at the margin (i.e. still more lay-offs every week, albeit fewer) I just don't see where those 2/3 of GDP are supposed to come from.

- It's not just unemployment. People are also saving more.

The question here is, of course, what a new equilibrium savings rate would be. Right in the heart of the credit crisis we saw it jump back up to 6 percent, which is unlikely in the long run. But maybe something around 4 percent? I mean, that's still 100% more than in 2005 or 2006. Not only are people out of jobs the little money that they do earn they also don't spend.

The question here is, of course, what a new equilibrium savings rate would be. Right in the heart of the credit crisis we saw it jump back up to 6 percent, which is unlikely in the long run. But maybe something around 4 percent? I mean, that's still 100% more than in 2005 or 2006. Not only are people out of jobs the little money that they do earn they also don't spend. - There is a very scary housing picture. Mortgages are in default and haven't even hit the foreclosure stage yet b/c... well, what does a bank want with a house? The mortgages in default now are increasingly of higher quality. It's not just the sub-prime people anymore. The ratio of going into default once a mortgage payment is 30, 60, 90 days overdue keeps rising, and the rate of people staying out of default once they have done a reworking of the terms of the mortgage keeps declining. So the housing picture could still get a lot worse. People won't have as much equity and banks similarly won't have a lot of collateral they can rely on.

- Banks are rationing credit. The credit markets aren't frozen but we're seeing a lot of pruning at the lower end of the credit spectrum.

- Currently there is a lot of G (government spending.) That's going to end sometime.

- Export might pick up, seeing that the USD is extremely weak.

- ummmm.....

But the stock market has rallied in the face of all of this, up over 63% since the low in March and 20% since the beginning of the year. Last earnings season was very positive since a lot of companies beat analysts' earnings estimates through a combination of cost-cutting, accounting

Since then I have essentially said that this next earnings season will give guidance and show that the market has gotten ahead of itself. Companies will disappoint and the market will correct. Except, an astounding 78% of the S&P 500 companies have beaten consensus estimates so far. What the hell? No wonder the Dow is close to breaking 10,000. Argh!

Finding the odd one.... nevermind. there is no odd-one out anymore

Mexico had looked like this:

Now it looks like this:

Now it looks like this:

The equity markets kept grinding higher and the Peso, after its sell-off has followed suit.

The equity markets kept grinding higher and the Peso, after its sell-off has followed suit.

Here is what Korea looked like:

Here's what it looks like now:

Here's what it looks like now:

Here the Won had kept appreciating while the equity markets sold off. Now they're back (although Korea is the worst-performing market in the MSCI Emerging Markets month-to-date.)

Here the Won had kept appreciating while the equity markets sold off. Now they're back (although Korea is the worst-performing market in the MSCI Emerging Markets month-to-date.)

Maybe the way to play this sort of thing is through a relative value trade.

The NY Times Needs to get a copyreader

A little more than a month later, the funds, filled with some of the most explosive and high-risk securities available, imploded, evaporating $1.6 billion of investor assets and setting off a financial chain reaction that has rattled global markets, caused more than $350 billion in write-downs, cost a number of executives their jobs and culminated in the demise of Bear Stearns itself.

The Times needs a copy-reader. "[T]he funds, filled with some of the most explosive [...] securities available, imploded"? Imploding is the exact opposite of exploding. Unless, of course, the securities were highly explosive but failed to deliver and the whole thing just imploded instead.

Ahhh.... the joys of stickling on a Wednesday morning....

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Dani Rodrik does it again

"Financial markets discipline governments. This is one of the most commonly stated benefits of financial markets, yet the claim is patently false. When markets are in a euphoric state, they are in no position to exert discipline on any borrower, let alone a government with a reasonable credit rating. If in doubt, ask scores of emerging-market governments that had no difficulty borrowing in international markets, typically in the run-up to an eventual payments crisis.

In many of these cases – Turkey during the 1990’s is a good example – financial markets enabled irresponsible governments to embark on unsustainable borrowing sprees. When “market discipline” comes, it is usually too late, too severe, and applied indiscriminately."[bold emphasis mine]

I whole-heartedly agree. As to his larger point: I wonder what appointing a finance skeptic to head the Fed would look like? Who would he have in mind?

Monday, October 5, 2009

Find the odd one out

The data bear out this relationship for the most part. Bovespa, for example shows strong co-movement with the Real.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Communism

So why??? are we perfectly willing to discuss and defend capitalism on a theoretical level while ignoring the outcomes or, if not ignoring, viewing them as deviations from the norm, noise, dirt that muddles the theory a little but in general the theory holds... why are we willing to do that when any time someone would want to seriously discuss socialism or communism the next sentence spoken is: "Communism is a great theory but it doesn't work in practice." Sure, the failure of communist experiments have been huge but the failures of capitalism like e.g. the past crisis (or the fact that wealth is so unevenly distributed around the world or even around this country and that millions die of hunger and disease, every year) have been nothing to sneeze at either.

Notice that I am not advocating communism or socialism (although I am hazy on what exactly socialism is--I am in favor of a socially conscious and responsible capitalist approach.) I am merely wondering why, as a society, we are fine arguing on the basis of theory, ignoring the unfavorable outcomes in capitalism's case but are not willing to do so when talking about communism.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Soda Tax

All in all I'm probably in favor of this. People don't really need to drink this much soda and soda is so dirt cheap, it's not going to send anyone to the poor house. I do wonder how effective you could make this and what some of the possible unintended consequences would be.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Mortgage Crisis Redux

1.) Over the past few years one of the great financial innovations created was Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS.) What you do is the following:

2.) Of course, back when, all these people with no income and no assets got a mortgage. Makes sense if I'm the small bank. I do the mortgage, sell it to the big bank. If they are too dumb to buy it, not my problem. The big banks... well, they just bundle it all together, slice it up, hope all goes well and sell it to someone else. Not their problem anymore.

3.) Now all those NINA (no income, no assets) people start to default on their mortgages. Surprise!!! The big bank gets the house and tries to sell it. But people are defaulting on mortgages left and right. Everyone who wanted a house got a house and everyone who can't pay for it is defaulting. No one wants to take the house off the big bank's hands.

4.) Of course for the owner of the small pots of money that sucks. More people than I thought are defaulting on the mortgages (so I don't get as much money every month) and the collateral they leave behind is worthless, too.

5.) Okay fine, Ima try to sell my MBSs. But EVERYONE owns these securities. They become worth ever less.

6.) If you're a big bank that owns a ton of these MBSs the value of all your asset drops. But the government requires you to have a certain amount of assets in the basement just in case someone comes and wants to withdraw all their money. But now you don't have that anymore. So either you have to sell off business units or... or who knows.

7.) Except for no one wants to buy your stuff now b/c everyone else owns the mortgage backed securities and is strapped for cash.

8.) Okay, so the first thing I, a big bank, stop doing is lending out money to businesses. I have no idea who else owns how much of this stuff and isn't going to pay me back.

9.) And that's what Ben Bernanke means when he says that the arteries of the economy are frozen.

So fast-forward to a year later. We're possibly slowly recovering. Everyone has been slapped on the fingers, and a lot of big banks are still hurting (not to mention the rest of the us.) How do I, as a big bank, make up for all the losses, all the jobs lost, all the bonuses forgone? Oh, easy!

The NYT reports:Wall Street Pursues Profit in Bundles of Life Insurance

Ummmm.... seems like a great idea? You bundle all these payments, slice them up, sell them to a ton of peop.... errrrr....

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

Thursday, April 30, 2009

China, the fiscal stimulus, and development

"Caterpillar Inc. Chief Executive James W. Owens says [...] China continues to have a great need for infrastructure and that projects there could start much more quickly than could similar projects in the U.S. 'It's something like nine months [in the U.S.] versus nine weeks' in China, he says."

This is, obviously, what the (American) administration means when it announced fiscal simulus for "shovel-ready" projects. Where between 9 weeks and 9 months does shovel-ready lie?

Here's another interesting take on what happens when you don't have any shovel-ready projects, errrrrr, shovel-ready:

"In Los Angeles County, cities are buying federal stimulus funds from each other at deep discounts, turning what was supposed to be a targeted infusion of cash into a huge auction."

In contrast, this is why the Chinese stimulus seems to be coming on-line so much faster than the American one (again from the WSJ article):

"The swift start on the Xiangshan Island Bridge project reflects years of preparatory work, a top-down administration that tolerates little dissent and a pipeline of projects.

Indeed, by the time building on the bridge began, it had been being planned for 15 years.

'China has a strong pipeline of well-prepared projects,' says Robert Wihtol, China country director for the Asian Development Bank." [emphasis mine]

I've always struggled with the (apparent and maybe latent) debate and/or contradiction in the development literature over what's better for development, democracy or authoritariansim. Here are some excerpt's from A.K. Dixit's excellent "Evaluating Recipes for Development Success" for some background:

At a broad and general level, cross-country regressions yield mixed results on the

question of whether democratic or authoritarian governments are better for growth. For

example, Barro (1999, p. 61) found a relatively poor fit and an inverse U-shaped relationship.

He suggested that “more democracy raises growth when political freedoms are weak, but

depresses growth when a moderate amount of freedom is already established.”

[... bla bla bla, some stuff about pathways, local knowledge, the usual good things]

These are just a few examples from a vast literature, and they add up to a message that

is pleasing and even uplifting to many modern academics and policy practitioners alike –

democracy is good not only for its moral and human appeal, but also for its economic

performance. [...] But not so fast. There is an equally impressive emerging literature that makes a serious case for authoritarian governments and institutions when it comes to starting growth and development.

[...]

First a conceptual matter: what feature or features of policies are important for good

economic outcomes, regardless of what kind of government makes those policies? Here much

of the literature does find one point of agreement: credibility of commitments is vital. [emphasis mine]

Indeed, it appears that China retains several aspects of democracy at

lower and middle levels of institutions and economic policymaking: there are some genuinely

contested elections at these levels, press criticism of officials at this level is tolerated and perhaps even encouraged, and corruption is swiftly and severely punished when detected.

Only at the top level is the Communist Party’s rule rigid and unchallengeable."

I would argue that the Chinese administration for all its shortcomings does have very good credibility of commitment. In fact, I don't quite agree with Merrill (was it Merrill?) when they expect China to grow at 6.5% this year. If the Chinese administration says China will grow at 8%, they will grow at 8%, I think.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not a hater of democracy--in fact I pretty much adhere to Sen's view that development must essentially be viewed as freedom--and China obviously has a horrible score here but I think the Chinese set-up has some lessons. Not only did it manage to deliver the biggest pro-poor growth miracle in the post WWII era (or maybe ever) it seems to be good at making the stimulus work, too.

I'm not really sure about all the development implications, different definitions of development, effects on growth, effectiveness of growth for lower income strata, &c. But I do believe that China is going to come out of this crisis much earlier than the rest of the world and that the rest of the world will owe something to China in terms of dragging us out as well.

How is low-income fiscal stimulus delivered?

I’m just reading a brief Merrill March update on Thailand. In it is the following section:

Therefore, consumption remains at risk with an expected rise in unemployment.

However the Bt2,000 allowance for low-income earners, distribution of which

began from the end of March, is expected to cushion consumption in 2Q. The

total amount is Bt19bn. So far, Bt11bn or (0.5% of quarterly GDP) has been

converted into cash”

And that got me wondering: When governments provide fiscal stimulus in economic crises or just simple fiscal countercyclical measures and when they provide this to the poorest strata of society (as they should) how do they do this? I’m not sure how this looks in Thailand but I’m sure in very rural economies a significant number of workers (especially among the very poor) don’t have checking accounts. Or if we’re talking about slums then people won’t have mailing addresses where checks can be sent either. And I doubt they just wire the money. So then how is fiscal stimulus delivered to those people. Does someone drive around with an armored truck into a favela and hands out cash? That person would never make it out! My guess is fiscal stimulus is not delivered to the very poor, just to the poor that the state can “see” (in a Jim Scott Seeing Like A State kinda way) through its administrative matrix. And then how do you solve that problem? There obviously is a role for microfinance – providing people with access to financial institutions, not just credit but checking and savings accounts. But still… people without IDs, without proof of address (which can be a large part of a poor country’s population)… they’ll just be excluded.

Friday, March 13, 2009

Market Catalysts

THE TONE AND DIRECTION OF THE MARKETS REMAIN LINKED TO THE INVESTMENT COMMUNITIES VIEW OF THE BANKS, AND FOR NOW NEWS STORIES OF GOOD FIRST QTR EARNINGS AND POTENTIAL ADJUSTMENTS TO THE MARK TO MARKET ACCOUNTING HAVE HELPED ALOT. WE'LL SEE!”

In my mind that pretty much hits the nail on the head, except for I don’t see this quite as positively. People are sick of the continued pain and want to believe in a rally. I think that there are still too many systemic risks. In my mind the recent rally is due to:

a) mark to market rumors--buy the rumor sell the fact

b) Citi (and by now I guess BoA and JPMorgan (?) headlines of profitable first quarter, which are likely misleading. Citigroup claiming that it is profitable (pre write-downs, mind you) does not make a summer. Will there really not be any more writedowns? Have accountants really priced in increasing mortgage delinquencies due to ever-rising unemployment? I have a hard time believing that.

c) oversold levels after a week of straight declines. 666 was really low after the mkt had just collapsed.

So while you might be able to make money if you’re good at timing the market (unlike me!) I don’t think this holds. Incidentally, gold tells the same story as it keeps rising after dips.

Saturday, March 7, 2009

pound vs dollar

a) The biggest industry in the UK is banking. Banking as a whole is not particularly profitable and currently banks are particularly precariously perched. We have seen what can happen when Bear was force-married to JPMorgan and when Lehman went bust. In the US a lot of initiatives have been... errrrr... initiated to deal with struggling banks. For example:

- The Fed has aggresively cut interest rates. That makes the yield curve nice and steep. Essentially that is just a way of saying that long-term interest rates are high while short-term rates are low. Banks can borrow at ST rates and lend to you and me at LT rates. The difference is theirs to keep. So steepening the yield curve makes banks more profitable.

- Treasury has injected billions of capital into banks with the (inappropriately named) Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP.) So banks have gotten a lot of help that may (emphasis on _may_) enable them to weather the storm.

- The Fed and Treasury have issued guaranteed for losses on certain assets that banks own.

In the UK banks have, as to date, not received as much support. Making the British economy very vulnerable to a sharp slowdown, quite possibly sharper than in the US where a lot of the pain has already been borne. If an economy grows slower investments in that economy tend to be less profitable. I.e. I am not going to buy British pounds to either buy British stocks or to directly open a factory or something if I don't think I'll get a good return on that investment. The reduced demand for the pound from that side drives down how much people value the pound vis-a-vis other currencies.... including the dollar.

b) In the general climate of risk aversion that is hitting capital markets these days--people are just afraid to put their money in anything but the safest assets--many people sell off what they have and either stuff their money in the mattress or invest it in the safest of safe assets... for better or worse still United States Treasury bonds. Since such a large proportion of the world's investments come from the US a repatriation of capital (i.e. selling off your stocks in Brazil, exchanging your reals back to dollars and putting the money in your safe) means that many currencies decline versus the dollar as demand for the dollar goes up.

This is a very peculiar phenomenon. Mostly, if a country is facing an imminent economic crisis its currency will decline as investors pull out of the country. In this case, however, as the US crisis deepens it makes US investors more jittery about their returns while simultaneously weakening _other_ economies. These are the two biggest reasons why the pound and other currencies are weakening against the dollar even though the US is in such bad shape.

Friday, February 13, 2009

Shipping

The Baltic Dry Index is an index that tracks shipping costs and, in the short term, is a good approximation for trade volumes, seeing that shipping supply is relatively fixed in the short run. Is this a first time of trade at least picking up again after having deviated soooo much from the trend and now reverting? I'm aware that there's no shortage of wanting to find signs of recovery, i'm just finding it interesting.

After looking a little bit I find a comment from one of the independent research houses to whom we subscribe on just that topic. Trusted Sources says:

"The recent rise in freight rates for dry bulk commodities has sparked misplaced optimism that Asian demand is picking up and that global trade is rebounding. The higher rates are due only to a limited recovery in iron ore shipments from Australia and Brazil to China and therefore do not signal a broad return to robust consumption. Freight rates, which are down more than 90 per cent from their highs last year, will not see a sustained recovery until the oversupply in the shipping market is absorbed or dissipates via contract cancellations or outright scrapping.

As our trusted source notes, the market has yet to hit bottom and dry bulk fundamentals do not point to a recovery in freight rates this year. The turmoil in the shipping market – with firms going bankrupt, broken chartering arrangements, newbuilding order cancellations and delays – means that, at least over the next year, freight rates will be less an indicator of underlying commodity demand than a reflection of the continuing shakeout in the industry."

Thursday, February 12, 2009

That'll be the day....

Reuters: US AND UK "AAA" RATINGS "BEING TESTED" BECAUSE OF SHOCK TO GROWTH -MOODY'S

My friend Priya seemed really alarmed by this... due mostly to a misunderstanding where she thought this was for corporates. Which led to the following fun exchange:

me:

"I'm not sure how much impact a downgrade of treasuries would have on the

corp CDS market. A little for sure but... I don't think much else. And

Treasuries are held mostly by sovereigns (as reserves), I think, and I

don't think they care particularly what moody thinks. Plus, as the

Chinese have pointed out, you don't have much else of an option. What're

you going to hold, sterling? Bund auction failed yesterday so that

doesn't seem too smart to hold either.

Imagine US treasuries got downgraded? I mean, makes sense but..."

Pri:

"the chinese are in for deep trouble!"

me:

"Well yes and no. I mean... they can afford to just keep holding those Treasuries till maturity so they're not _actually_ losing money. In the meantime, as Treasuries trade down they'll "lose" reserves (b/c the T-bills they hold trade as less) but as we move closer to maturity those same T-bills will trade back to par. And I don't think they care _that_ much whether they 'lose' a few billion b/c of what essentially just amounts to mark-to-market accounting. Unless, that is, the US is insolvent in 30 years and can't pay anyone back and also not get new debt, hahaha, errrr...."

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Fwd: Landon Lowdown: Bernanke drops a bombshell

----- Original Message -----

from Ken Landon, J.P.Morgan Strategy, NY (Feb 10)

This did not come across Reuters or Bloomberg, but Fed Chairman Bernanke just stated during Congressional questioning that any firm that participates in TALF will be held to all the restrictions imposed on TARP recipients, including compensation limits. He said that firms will be audited to make sure that they comply with heightened restrictions.

This will be another confidence killer.

Kenneth Landon, Feb 10, 2009

This is a bit of an illustration how financial mkt ppl think about these things a little differently from many other ppl I know. Most ppl would probably say "yes, if you participate in TALF (a gov't lending facility that is supposed to shore up the asset backed securities market) you should take restrictions" whereas this guy seems to think that "dude, if you put on all kinds of restrictions for companies and we can't see ex-ante what they are... people aren't going to value a stock like that. B/c for example the gov't could just at some point come and restrict your dividend that you're supposed to get as a shareholder." (which is what they did... and there may be other things like that that they come in to do later.) I, for one, however, am not really concerned with equity markets but rather with recovery of the underlying economy. Equity markets will follow or anticipate this... they will reflect it in some way sooner or later. So in that way I really don't think Bernanke dropped a bombshell.

ahead of the second round of bailouts

As far as I remember that's exactly the same point Paulson and Bernanke made. It's true -- 350 billion haven't done anything so far apparently. The question then is why it would help now. To be fair, we don't know what the counterfactual is. Maybe we'd already be in default as a nation and in shambles as an economy without it. Will be interesting to see what Geithner has to say at 11.

Monday, February 9, 2009

Interesting...

Kinda fun to think about, seeing that I just said that that was my belief on Friday. Wonder if I should put my money where my mouth is and put some $$$ behind that. Now I'd just have to figure out how to put that trade on in my little E*Trade account, haha.

Friday, February 6, 2009

Question about Turkey and IMF note

"Turker,

I read your note about what would happen if the IMF deal were to fail in Turkey, and I don't know if I completely understand your reasoning. In your last paragraph you say that no IMF deal means lower growth and a weaker TRY. While I agree with the latter I am not sure how your arguments imply the former.

You say that no IMF deal could be perceived as an unwillingness to clamp down on easy fiscal policy. But isn't, especially in a downturn, easier fiscal policy stimulative for growth? Additionally, the lower TRY would support the (admittedly small) export sector. The one channel through which I could see easier fiscal policy constricting growth is via (as you mention) higher rates crowding out investment. However, a) you argue in the previous paragraph that even as Treasury has borrowed strongly yields have refused to rise too much and retail investors as well as banks are still eager to move into bonds. Do you see this changing dramatically? and b) what do you think are the relative effects on growth of looser fiscal policy? Presumably even if 1-to-1 crowding out were to take place there would be no impact on growth, at least not in the short run (as private investment decisions would likely spur growth in the LT and government spending may take the form of consumption.) I'd be interested in your opinion.

Cheers,

Holger"

I'll keep you updated on what he says.

short-term

I stand by my earlier sophisticated technical analysis (see here, same graph as above). The S&P has been range-trading since December and barring major developments will probably continue to do so. It's only if it breaks out above 900 or below 800 that I will revise this view (from a technical perspective.) This, btw, is the theme we call "break-out or crap-out" internally.

Notes from Mexico conference

Carstens first highlighted some negatives before illustrating reasons for optimism.

The Bad News:

- There has been a distinct downward revision in growth expectations after the Lehman collapse. - IMF forecasts shrinking trade levels for the first time in Mexico.

- Export growth collapses from 9% growth in Aug 2007 to -9% contraction in Dec 2008 – a severe downturn.

- Commodity prices are weak bringing down earnings.

The Good News:

- The downward growth revision in Mexico and other EM has not been as severe as in developed economies.

- The banking system is healthy and lending in Mexico is still expanding (although at a slower pace than over the past few years)

- Despite weak commodity prices, public finances remain strong: the budget is nearly balanced

- Debt as a % of GDP is decreasing

- Mexico has done a lot of work to shift its debt profile towards a longer horizon

- The good public finances have allowed Mexico to be proactive and, unlike in other crises, use countercyclic fiscal policy. These policies, although not as large as in the US, are commensurate with the stimuli other countries have enacted and he estimates the impact on GDP to be about 1 percentage point

- Inflation is under control and continues to come down, leaving room for easier monetary policy.

To me the most important points to me seemed to be that

a) the government this time is much better positioned to deal with a downturn than in other crises and has already demonstrated the will and the power to implement fiscal stimulus through the enactment of various programs.

b) The banking sector is not as vulnerable than in the US or Europe and continues to lend so we’re not seeing the same choking effect on companies via a freezing of credit markets.

All in all a pretty favorable assessment corroborating my view even though we would have to look into details to determine how much better Mexico is positioned than other countries.

I loved, btw, that someone else at the conference highlighted (highlit?) that once of the big advantages that Mexico has is that it is no stranger to crises, haha.

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Initial jobless claims

Actual: 626,000

Previous: 591,000

Consensus: 580,000

626 thousand new people went to the unemployment office over the past week. That, ladies and gentlemen, is what the recession looks like. What I don’t get is how with a previous number of 591K, the consensus was for 580K new unemployment claims. Who are these people who think there would be less unemployed this week than last?

Goldman's "skinny" (a comment they send out on most pieces of economic data) on this:

"BOTTOM LINE: Another jump in claims shows continued deterioration in the labor market (though not directly relevant to tomorrow's payroll report) while companies managed even larger gains in output per hour worked than expected from those who remained on the job."

I remember reading an op-ed or something by Krugman in 2002 or so on how the US got out of the last recession and "productivity" was sortof the key. And I remember him railing against the use of the term "productivity" when what the reality is that people are being scared into losing their job and those who don't lose it are made to work longer, harder hours. B/c it's not like some crazy total-factor-productivity-enhancing (you like that?) supernew technology came out all of a sudden that caused a spike in people's productivity. And basically it amounts to saying: "Work harder and if you don't you're gonna lose your job and you don't have any say in this. And those who don't lose their jobs need to pick up the slack." AND, obviously these situations are sticky. Just because the downturn is over doesn't mean that firms will revise down their expectations from workers.

The bad news: Looks like we have the same situation again and workers will be permanently placed under more strain again.

The good news: If it's worked (haha, npi) in the past maybe we have a way out of the recession. Maybe we won't even have to, as Obama suggests, think what we can do for our country, maybe that thinking will be done by our companies for us and all we have to do is do what they tell us to.

Compensation Caps

Some further thoughts on these, however:

- The way the regulation is worded, as far as I'm aware, it's the top 5 people who are capped. My boss thinks that banks will get around this. He think the incentive is going to be very large for banks to say: "You know what, we've come to realize that a completely flat structure is best. From now on we are all vice-presidents here at Morgan Stanley."

- You can imagine a scenario in which a faltering bank does not take TARP b/c it would limit the top five people's pay. I mean, Goldman for example, said that they might actually give the TARP money back. There's principal agent problem, and I don't know if there are any mechanisms in place to solve it.

- As for the argument that, as Meredith Whitney of Oppenheimer said, a cap on compensation would lead to a brain drain in finance, there are three considerations:

a) I somewhat doubt that. A college grad, even one of the "best and the brightest" is not going to start at Goldman b/c maybe 20 years down the road he would become CEO and make tons and tons and tons of money. And a CEO is not going to quit the line of business b/c of the pay cap -- the opportunity cost is too high. So I really doubt that partial equilibrium analysis has much validity.

b) I somewhat doubt that the marginal revenue product of (financial) capital is very large at these levels. What I mean is that I doubt that the extra dollar (or million) spent on executive compensation gets you _that_ much better of a CEO, someone who is _that_ much better at steering the ship. The fact that the market produces this outcome is obviously an argument for this but I'd like to think this through and see if there are not other incentive structures that could produce this type of equilibrium but that also imply that it might not be efficient. Plus, I wonder how much worse the next in line guy (who would take the job and not also leave) would be.

And finally c) What would happen if all the "best and the brightest" as Whitney says were to leave the business and figure out how to make money elsewhere? First, if it hadn't been for pretty smart and really driven people who had invented structured finance as we know it we wouldn't be in this mess. And second, what are the general equilibrium effects of all the "smart" people leaving finance and going into other business, law, politics, public service... I doubt the net effects would be negative.

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Fiscal Stimulus

"We have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent

before and it does not work ... After eight years of this Administration we

have just as much unemployment as when we started ... And an enormous debt to

boot! -- Roosevelt's U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, testimony to

the House Ways and Means Committee, May 9, 1939."

That is something to consider in the current climate and when trying to weigh whether a fiscal stimulus is likely to be efficacious but on second thought, the argument is totally spurious. Morgenthau has no idea what the counterfactual would have been like. So claiming that "it does not work" is just uninformed. You can make all sorts of arguments about crowding out about disincentivizing productive capital through an excessively regulatory environment, about an onerous tax burden for future generations, &c &c &c but just claiming that it is not working b/c unemployment is stable... that's just dumb. I mean, imagine we'd have a fiscal stimulus plan that had stabilized unemployment at 6.5% and we weren't at 7.2% right now (with more probably to come.) Would anyone say this wasn't working? It's such an elementary mistake.

Housing

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Bank Market Caps

You thought Morgan Stanley or Goldman did so poorly that they were forced to become bank holding companies? You think the credit crisis is an American bank phenomenon and that European banks are not as vulnerable? Look at JPMorgan or Goldman, then look at Barclays or RBS. Then again, look at Citigroup. Yeah, it seems totally great to pump more and more and more money into them.

Friday, January 16, 2009

I want a lifeline too!

" Jan. 16 (Bloomberg) -- Bank of America Corp., the largest

U.S. bank by assets, posted its first loss since 1991 and cut

the dividend to a penny after receiving emergency government

funds to support the acquisition of Merrill Lynch & Co.

The fourth-quarter loss of $1.79 billion [...]exclude $15.3 billion

in losses at Merrill, which was acquired earlier this month.

The losses, coupled with the U.S. lifeline of $138 billion,

put more pressure on Chief Executive Officer Kenneth D. Lewis to

make the takeovers of Merrill and mortgage lender Countrywide

Financial Corp. pay off."

I dunno, but getting government help b/c you're too strapped for cash b/c you bought two faltering institutions... that seems kinda wrong! That's like if I buy myself three Ferraris and then ask my parents to pay for my rent b/c I can't afford it anymore and when they ask me why I bought the Ferraris in the first place I say: "I had to. They were such a steal, it would've been stupid not to buy them.

AND: BoA makes a loss... but that doesn't include $15.3 billion, repeat fifteen point three BILLION dollars, in losses from Merrill. Wow, that Merrill Lynch was a real steal for them!

But so what exactly is this kind of lifeline? The gov't just injected $20 billion, which apparently will take BoA/Merrill only about a quarter to burn through and then they get $138 billion as a "lifeline"? What is as lifeline? Is it like a loan? Yeah, as if that's gonna pay back! So then here's why all of that happened.

"Bank of America officials then told regulators last month

that the Merrill deal might be abandoned because of worse-than-

expected results, Lewis said. The government insisted the

transaction proceed because its collapse would create new

turmoil in the financial system, he said."

That makes real sense! "Nonono, you have to go ahead with this b/c otherwise it'll be the end of the world. Don't worry, we'll help you now. We're sure you won't run into a wall a few months down the road and need to split everything back up again. That never happens. Look at Citibank, that didn't happen to them! Errrr.... wait a second...."

And then... and then:

“'We just thought it was in the best interest of our company

and our stockholders and the country to move forward with the

original terms and timing' for buying New York-based Merrill,

Lewis said today."

The country??!!! Don't act as if you care about the country all of a sudden. If you subscribe to a relatively pure capitalist system (, which as a bank you surely), it's all find to say that you're just looking out for your shareholders. But don't pretend all of a sudden you're doing stuff b/c it's good for the country! If you wanna do something that's good for the country, axe the bonuses, institute government-employee payscales (b/c pretty soon you'll be government employees) and let some people keep their job instead of axing them all -- that's something that's not good for your shareholders or you but it's good for the country.

This week

Nonfarm payrolls were down 524,000 in December, pretty much right on the consensus view. They'd been down 584,000 in January. So bad. At least the decline is slowing? But half a million. Half a million new unemployed in December. Change in manufacturing payrolls was 149,000, up from a revised earlier number of 104,000 and really disappointing the survey, which averaged at -100,000. So I guess we can say manufacturing has been hit harder than the rest. Unemployment surprised on the upside at 7.2% (estimate was 7%, prior number was at 6.8%.) So yeah, the employment picture is not pretty.

Retail sales in December absolutely plummeted. Down -3.1%. Estimate was half that. So economic activity also is stalling pretty badly.

On the other hand, mortgage applications were up by 15% in the Jan 9th week. Up from -8.2%. That, to me, is very good news. That'll take a good while to filter through but I see it as the first step in stabilizing the housing market. And I see that as the first step to recovery. B/c, oh I dunno.... maybe someone like Citi wouldn't lose $8billion a quarter anymore.

Citi better give me my money back

" Jan. 16 (Bloomberg) -- Citigroup Inc. posted an $8.29

billion loss, twice as much as analysts estimated, and said it

will split in two under Chief Executive Officer Vikram Pandit’s

plan to rebuild a capital base decimated by the credit crisis."

What I want to know is how they lost all the money. Is it still writedowns on MBSs? Is it trading (like at Deutsche)? I dunno, man, but 8.3 billion is a lot of money. Those guys already got 45 billion in tax dollars (slash debt dollars.... but ultimately everything is tax dollars), which could have gone to schools, housing relief (to stabilize the mortgage mkt? what a novel idea!!), unemployment benefits to make the recession less painful--an automatic fiscal stabilizer--something. I mean 45 billion.... that's a hundred an fifty bucks from every American. Split those guys up, sell the pieces, limit the losses and let's move on.